By Bradford F. Spencer, Ph.D.

INTRODUCTION

Leadership is a much written about topic. The popular business magazines and indeed, some rather well selling books are often focused on specific leaders. In America, we often deify or crucify our leaders, and our business leaders are no exception to this foible.

However, today’s research into the true causes of the patterns of what molds leaders does not focus on nearly enough. Certainly the scientific community looks down on the “research methodology.” The fact is the research often consists of interviews by business professors asking prominent captains of industry to speculate on why they are so different. To give credit where it is due, most executives admit they have no clue — before they continue the dialogue to try to help the struggling researcher find the childhood incident which led to the drive that has set him or her apart. No wonder the conclusions are both suspect and not helpful to those asking what they do to improve themselves. This is where the approach of Dr. David McClelland differed so dramatically.

This series of articles is designed as a pre-reading for the workshop (Leadership Process: Motivating Achievement) designed to both explain and cover how to apply the extensive work of Dr. McClelland and his students. For that reason much on detail “how to” implement the findings will be left for the lectures and interactions of the workshop. Our experience is that an overview of this extensive body of knowledge will give the group a running start, thus allowing much more territory to be covered in our limited time.

Interestingly enough, the initial research was not about the systemic and predictable causes of leadership at all. Nor was his interest in business, and certainly not business applications. More will be said later as to why this social scientist toiled away in relative obscurity and to this day his name is not recognized by many — but most of today’s works of substance cite his contributions. Certainly he was recognized as a giant among his peers and his position as head of the School of Social Psychology at Harvard University provided him with a unique platform. He used this platform to forward his work rather than to build fame.

The sheer differentiation of businesses and the demands on their leaders in differing times and marketplaces makes comparison a daunting task. The unpredictability of the battlefields they find themselves on compounded by the changing competitive landscape expands the difficulty. Fortunately, we have generally accepted definitions of success as defined by Wall Street and its counterparts in every major free market nation which make it possible to compare results across continents, and indeed, oceans.

When people of good will do their best and succeed beyond their peers it is only natural to seek to find if a pattern exists. A primary reason is to create an edge by standing on their shoulders in developing the next generation of successful leaders. It seems the general public has in a rather cynical (but perhaps understandable) fashion bought the myth that the drive is to dominate one’s fellow man — or simple greed — is the explanation behind what drives executives to positions of power.

The retailing of this perspective yields no help to the true student. Explaining the common obsessions that brought them to the position where they are surprised by the acclaim and often reluctantly find themselves on the covers of magazines, is the question we are setting out to answer with the implications for every managerial and executive level. Successful leaders recognize at a profound level the article is truly not about them, but rather a way to sell magazines while covering a business story. Pictures of the corporate headquarters do not jump off the newsstands.

What this series of articles does not attempt to review is the root causes of the numerous reasons for failure once the pinnacle seems to have been reached. Conflicts so varied and deep as to defy a research process seem to be at work. But we think we have hints as to why the great often fall. However, the reality is that those driven to make businesses succeed tend to stay successful much more often than not. We do think we have a modicum of insight into why that is. Frankly, it does not make for great headlines or even at times for interesting reading.

I apologize in advance if this series proves to be a bit dry and suffers from a few too many footnotes and charts. If you seek a study in the “management du jour” techniques, you are reading the wrong paper. What makes “the few” able to consistently elicit more discretionary effort, to hire better people and have systematically more motivated people with better results is what we are attempting to document. We have labeled the phenomenon “The Leadership Chain.”

INITIAL PREMISE

Right out of the gate, the initial premise is simple. Without question, the key to beating the odds against today’s challenges has to do with creating an environment that produces an “achievement aroused,” high performing workforce.

So what is the job of an effective leader? Is it to provide direction? To motivate? To challenge? “All of the above” may be correct, but they are limited views of what a leader is. Leaders do all these things. But what is the essential aim of leadership? It is to create a climate wherein people want to — are aroused to — produce great results, and seem to be driven to do it over and over.

This is the job of the leader — to create conditions wherein others produce great results, and they do it repeatedly. Reproducing these results over time is what produces greatness, in leaders, in organizations, and in people. The job of an effective leader is to stimulate employees to push themselves and accept personal responsibility to meet or exceed tough performance targets. It is to create organizations where people do things above and beyond the call of duty; where people are highly committed to delivering extraordinary results. In other words, great leaders systematically create highly motivated, high achievement aroused organizations.

RESEARCH

No body of research and practical application has come close to matching the profound impact of the work of Dr. McClelland, his students, and his many associates. McClelland is footnoted in literally every major work on leadership from Drucker to Peters to Kotter, and is recognized as the foundation upon which most motivational theories are based. Yet he is not well known. The reason his name is not a household word is not from lack of quality, but a genuine humility and commitment to high quality, high impact research, rather than the lecture circuit or publishing best sellers.

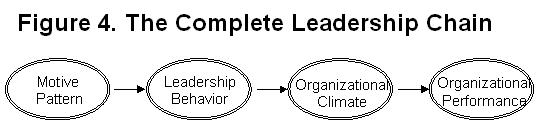

To explore the implications of this research and practice, we have summarized the research findings and their impact in this article. The end result is not intended to be a formula per se, but hopefully a clear and insightful look at a chain of cause and effect between individual motives, leadership behavior, and organizational climate, and how these dynamics drive organizational effectiveness. Leadership style is the critical link in the chain, connecting climate to motives to achieve organizational results. The findings presented in this article, and the research and practice contained within, form a chain of logic, the results of which provide a powerful guide for developing one’s own leadership and for creating and sustaining high performing organizations. You will learn to recognize what works and what doesn’t, and why.

“great leaders systematically create highly motivated, high achievement aroused organizations”

THE LEADERSHIP CHAIN

Consider for a moment the following scenario. You have just accepted the role of CEO of a company that has been struggling for many years. The prior CEO founded the company and, after many years and numerous waves of venture capital investment, was ousted due to an inability to meet the financial projections and commitments. The business concept is a sound one, and the people hired are quite talented. The market is growing and needs your product. Yet the company stands on the brink of extinction. Something needs to be done and you were hired to do the job.

The first thing you do is assess the business environment and discover that indeed the company has a good product and the market is ripe. The company has a clear strategy, one which will likely bear fruit. Unfortunately the organization’s climate is in shambles. Good people are leaving, morale has hit rock bottom and the people feel that the future is bleak. Your job is clear–get the company aligned around the strategy and get the people working together toward a shared cause. In other words, create a high performing work climate. The measure will be whether or not you meet the financial projections and commitments.

REVERSE ENGINEERING THE LEADERSHIP CHAIN

McClelland and his associates, fortunately, have a lot to say on the subject, and their research provides a clear guide for your leadership mandate. By connecting the dots of his research findings, a compelling chain of reasoning unfolds. We call this the leadership chain. There are four links in the leadership chain. To understand the logic, we will reverse engineer it by looking at the end of the chain, the organization’s results, and then move backward to identify the primary causal logic.

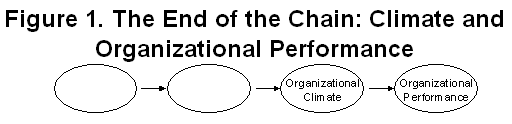

The End of the Chain: Climate and Organizational Performance

In the above scenario, the leadership chain is first evidenced by the organization’s performance–how is the company doing in the marketplace? If the company is not producing effectively, one contributing cause is often the result of a culture that is misaligned to the strategy manifested by a depressed organizational climate.

By climate, we mean those factors in the culture that affect people’s, motivation, desire and commitment. Because our focus is on the motivation role in leadership we will further specify the definition of climate to “a subset of measurable variables in the culture that directly affect motivation.” As we heard above, morale is low, people are concerned about the future, and we can predict that the organization is likely to feel unfulfilling and unrewarding to be a part of. In other words, the organization’s performance is directly linked to the organization’s climate. We will discuss the quantitative proof later, but anyone who has worked under these circumstances will attest to the relationship between the work environment (which we are narrowing to “climate”) and results.

Organizational climates can range from a structured, conforming, impersonal orientation to a more unstructured, collaborative, and personal orientation. Some climates emphasize group accomplishments, while others reward individual achievements. Climate, together with organizational strategy, dictate competitive advantage. While your strategy may be copied, it is extremely difficult to duplicate a culture and the climate.

So we have the last link in the chain: organizational climate to organizational performance. A misaligned climate resulting in depressed discretionary effort and collaboration towards goal attainment indisputably affects organizational performance.

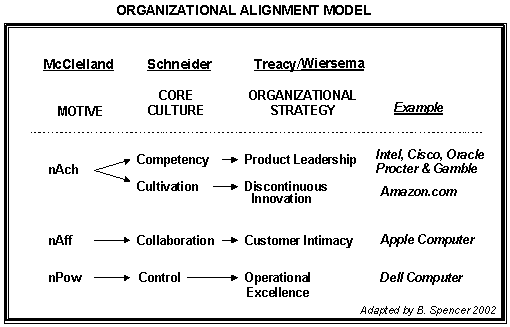

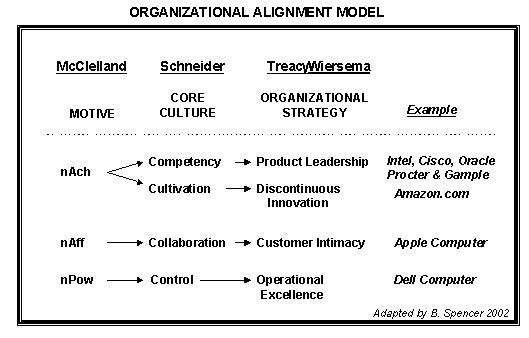

Climate, Business Strategy and Culture. It is important to understand the link between climate and the “bigger picture” concept of organizational culture. (I have included an appendix — with greater detail on culture as defined by the significant contemporary research of Dr. William Schneider. The reason it is not included in the body of this series is that while it is extremely important, I am limiting this discussion to the topic of motivation. Thus we can cover the issues we need to under the subset of culture we call climate. I am also leaving out an extensive discussion explaining the strategic “value disciplines” as outlined by Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema. (For a deeper discussion of these concepts, I refer you to their book Discipline of the Market Leaders.)

We will revisit the concept in greater depth, but for now suffice it to say, the theory states that ideally the culture lines up with the strategic imperative of the organization. Strategy for our purposes simply refers to the marketing decisions designed to give the products competitive advantage. If you choose “product leadership” (Intel, Sony) you have no choice but to adopt a “competence culture” to maintain alignment. If you choose to adopt an “operational excellence” strategy (Wal-Mart, WellPoint), your options of culture to remain in alignment is limited to “Control.” If you choose “customer intimacy” as the best strategy, (Southwest Airlines, Avon Products) the culture that will be aligned is “collaboration.” The last strategic option comes from Geoffrey Moore, the high tech marketing guru, and is referred to as “discontinuous innovation.” If that is your option, the only aligned culture is “cultivation.”

The model looks like this, but the detail is the topic of another book entirely:

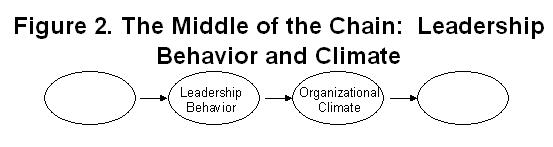

The Middle Of The Chain: Leadership Behavior and Climate

While other factors certainly impact an organization’s climate, the most potent impact is the behavioral style of leadership of the CEO and/or the leadership team. When organizations, like the one above, find themselves struggling, missing product deadlines, not responding to market changes, missing opportunities, etc., the most likely leadership response is fear and frustration. Out of fear and frustration, leaders resort to styles such as command and control, or blame. These coping styles, by their very nature, make the situation much worse. A strongly dominating or governing leadership style may not work to foster innovation, and a placating or involving style may not be best for producing timely results. In short, leadership style directly impacts the organization’s climate.

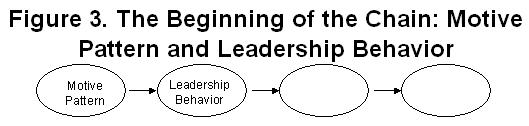

The Beginning of the Chain: Motives and Leadership Behavior

Finally, while many factors affect a leader’s style, the most significant variable is the thinking patterns, assumptions, world view, and personality of the leader. In other words, how a leader thinks and what drives his or her behavior directly impacts his or her style. (In these articles, to minimize gender bias, we will use “he” and “she” interchangeably.) We call this thinking pattern and drive–the leader’s motive pattern.

The Complete Leadership Chain

The above premises represent, in effect, three connections between four links on a chain of causality that have profound implications for leadership and organization performance (figure 4). They can best be expressed simply as follows: Your motive pattern combined with your ability to express those motives maturely and effectively has a direct impact on your leadership style. Your leadership style in turn directly impacts the organization climate you create, which in turn affects the degree to which people desire to achieve and perform in your organization.

In summary, effective leadership is the act of impacting clear and distinct organization factors, ones that are well within your control. Recognizing motive patterns and arousing motives towards accomplishing organizational results becomes easier when you understand the linkages between motive, leadership style, climate and behavior. Effective leadership can be learned through the direct application of a McClelland’s set of principles.

In the first part of this article, we will explore the first connection of this causal chain in detail and demonstrate the implication of this connection on leadership behavior. Then, each subsequent connection will be examined. Here is the outline for what follows:

Part I. The Relationship Between Motives and Leadership

Part II. The Leadership Chain Continued: The Relationship Between Leadership Style and Culture

Part III. The Leadership Chain Completed: The Connection Between Culture and Performance

Part IV. The Organizational Culture Alignment Model

Part V. Review and Summary of Conclusions

Appendix: A Brief History of McClelland and his Research

Appendix: A brief Summary of the work of Schneider and Culture

Part I

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MOTIVES AND LEADERSHIP

Before looking at the relationship between motives and leadership style, let’s first explore in more detail what we mean by “motive.” For our purposes it is neither a dictionary definition nor a reason for a crime.

What Do We Mean by “Motive”?

The term “motive” is a specific adjective in the behavioral sciences having to do with the repetitive underlying concerns or needs of a person. When you understand a person’s needs, you understand the recurring types of thinking this person engages in and the behavior that results. As an example, some people think about relationships, and tend to seek social and nurturing settings that follow that thinking pattern. Others are motivated primarily by their need to accomplish things of importance. They often would rather do it alone, if alone helps them meet their goals.

To understand why a person acts a certain way, we need to discover their patterns of thinking. Patterns of thinking affect the person’s patterns of behavior. Think for a moment about your first professional job. You probably were nervous, and you probably rehearsed in your mind over and over how you would act early on in the job. You probably even thought a lot about your first day, well before you got there. Why did you think about it? Because you had a concern. You either wanted to do well in the job, that is, be efficient or you wanted to make an “impression,” or you wanted to connect with people, or you wanted to avoid failure, or some combination of the above. These are thinking patterns. They reflect some set of underlying concerns. These concerns drove your thinking pattern and therefore, the patterns in your behavior.

“to understand why a person acts a certain way, we need to discover his or her patterns of thinking”

When we are talking about a motive, then, we are not referring to wants or desires or preferences. We are referring to “psychological needs” which must be satisfied for a person to function well. McClelland, in fact, defines a motive as a “recurrent concern for a goal state (measured in fantasy) which drives, directs and selects a person’s behavior.”

A motive is a “recurrent concern for a goal state (measured in fantasy) which drives, directs and selects a person’s behavior.” (McClelland)

Think about a time when you needed to be with someone you cared about. If the need was strong, you probably did whatever it took to be with that person. This was not a preference or a wish, but a strong need, which you took action to fill. It is needs and the motives which reflect the urge to meet those needs that was the focus of McClelland’s research.

How Motives Work

McClelland’s initial focus of study was to determine whether or not he could identify within individuals a motive or need, which, if impacted, would significantly increase their productivity. He and his associates did in fact identify such a variable. They called the motive, the need for achievement (described in shorthand as nAch). Such a need, as in all psychological needs, affects the patterns of thinking which drives the patterns of behavior. The fact is, there are no behaviors without precedent thoughts and thus, if you know your patterns of thoughts, your patterns of behavior in a given set of circumstances are predictable.

If you have a strong need for achievement, for example, you will likely seek ways of improving past or current performance, you will strive to better yourself, and you will seek to make significant and/or unique contributions to your work. Everyone has this need to some extent. This will occur in all parts of your life and it takes place unconsciously. What is interesting, however, is not that this need exists, but that different people have this need in varying amounts. It is also clear that different jobs require this to varying degrees and thus peoples “fit” varies dramatically. A night watchman with a high achievement motive will go stir crazy, drive others stir crazy with constant suggestions or get the meets met elsewhere. Moreover, one can, in fact, increase this need in others and in oneself.

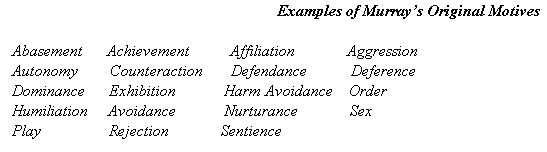

Drawing from a growing body of knowledge on the subject of motives, McClelland sought to understand the relationship between the need for achievement and a wide variety of effects, from the economic success of nations, to behavior of people under the influence of alcohol, to leadership effectiveness. In the latter arena (the subject of this series of articles) McClelland hypothesized that if you could understand and predict the motives that drive effective leaders, and then train people to alter or develop their drives, the result would be that any organization, and ultimately any society can be significantly enhanced. (For a detailed summary of the history of McClelland’s research, see the insert at the end of this article.)

In later studies of people and their motives, McClelland and his associates isolated two other specific motives, which, along with the achievement motive, account for as much as 95% of all social interaction. Since we are interested here in how people behave in organizations or at work, these are most relevant for our exploration. They are the need for affiliation (nAff), and the need for power (nPow). To understand the relationship between motives and leadership, let’s first explore these primary motives more fully.

The Three Primary Motives

Achievement (nAch). The need for achievement is characterized by the need to outperform others, high internal standards of excellence, and a desire to innovate. People high in nAch prefer to take responsibility for their actions, set challenging goals, and need a lot of feedback. They tend to be most successful in entrepreneurial settings, and in jobs that require high standards, efficiency, responsibility, and independent work. Their daytime and nighttime dreams (fantasies) are actually about these topics.

In Western society “achievement” is a value laden word which usually represents “good” as opposed to “bad.” Seeking the best and most effective way to rob a bank or commit an act of terror is lodged in nAch. In our usage it is the outcome the motive can be judged rather than the drive.

Affiliation (nAff). The need for affiliation is characterized by having a strong desire to establish and maintain close relations with others. People high in nAff often tend to be highly cooperative, supportive, and communicative. They tend to be most successful in job settings that require teamwork and integration. Their daytime and nighttime dreams are about establishing relations and avoiding the disruption of these relationships.

Again in Western society, “affiliation” is often viewed as a positive trait. For our purposes, the drive comes unattached to “good” or “bad.”

Power (nPow). The need for power is characterized by the need to influence others. People whose nPow is high tend to get significant satisfaction in influencing others, are often concerned for their reputation and position. They typically act in ways that generate strong feelings in others, both positive and negative and they influence others naturally through their actions. They tend to prefer jobs where they can have a direct impact on others, and as a result, are often well suited for management positions where success depends on their ability to influence. Their daytime and nighttime dreams are about these topics.

Again, in Western societies, “power” is considered a trait that comes loaded with baggage that makes it undesirable. It is the goals of this need to influence that determine the goals as positive or negative, but the “why” behind the behavior is nPow.

Because of our narrow definition, it is not the motive, but the goals which drive the ethics discussion.

Importantly, the power motivation in individuals can be divided into two types:

A. Personalized power — the degree to which a person expresses his or her power needs for personal gain and self aggrandizement;

B. Socialized power — the degree to which a person expresses his or her power needs to get something done for the greater good.

This distinction between types of power is significant, as will be seen later, because the former power drive can often invoke resistance in others and therefore be detrimental to an organization’s performance, while the latter is often essential.

A Hypothetical Scenario

In order to demonstrate the three motives in action, let’s look at a scenario to see how three different people in the same company might handle it. These examples are all caricatures and are purposely exaggerated to make a point.

Let’s imagine three people are driving to work who are involved in the same project. This is a project in trouble. It’s over budget, behind schedule, in disarray. Later, they will meet with the fourth person, their boss, a vice-president. No one slept well last night. Notice in the description below the different goal states each seeks, their differing thinking patterns, and the way that they direct and select different behavioral strategies to satisfy their dominant motive.

Mr. nAch is driving and traffic is a nightmare; cars are moving at a snail’s pace. The radio says there’s a wreck ahead. Within 5 minutes of being stuck, Mr. nAch had identified 2 alternate routes to work and he’s off the freeway in a flash, trying alternate 1. He can’t figure out why in the world all these other people would sit in traffic when there is obviously a better way, after all, they’ve been on this freeway a thousand times, just like him. Now, he’s way ahead of the game, feeling a little better for his efforts. “Sheep,” he mutters to himself. “Not only that,” he thinks, “but I’ve got the solution to the work situation. We’ve got to get the decision process to work better. Expertise is the key.

It’s no damn good that we take forever to decide everything. A geriatric unit makes a decision faster than us. Meetings about meetings. If I had the job, I’d get it done in no time. First, I’d reduce the paperwork 75%. No point to most of it. I already have the fastest turnaround of all the managers. I don’t know what they do with all their time. Maybe if they understood my system they could speed the process.” Mr. nAch felt very proud of the system he developed to process requests. It was unique to the best of his knowledge, and gave him a real advantage. Mr. nAch saw the light turn yellow and accelerated. “Made it,” he thought, “now if I keep it at 35, I’ll time ‘em all the way to Broad Street.”

Meanwhile, on another road, Mr. nAff is concerned that his group was demoralized by Mr. nAch’s and Ms. nPow’s tirades. He thinks, “Steve Smith’s wife just had a baby, and Mr. nAch did not take even a moment to congratulate him. He is so preoccupied that he doesn’t even seem to care about people. I just don’t understand people who don’t care about others.”

As traffic slows down to a crawl, he thinks about each person’s needs and preferences. “Smith is at a major crossroads in his career. His workload is increasing and yet he is being pulled to be at home more with his family. How will he create the balance he needs in life. Mr. nAch and Ms. nPow are almost unbearable. They are at each others’ throats. You’d think we weren’t on the same team. Yet they each have a legitimate concern, stemming from their highly aggressive goals, which conflict with each other. Unfortunately, this conflict has not been dealt with.

“We’ve worked together for years; we don’t want to become enemies,” he’d say to them later. “That’s the whole problem; we’ve lost each other’s support; who can work with all the back stabbing and anger.” Mr. nAff thinks about how he can help them resolve their differences. “I know people, how to get them back together, and once that happens, the rest will be easy. People can think again. No one wants to work when everyone’s angry and resentful of one another; what’s the point?” Relationships are the key.

On a different freeway, Ms. nPow was focusing on the company as a whole. “We’ve reached a major crossroads in our company,” she thinks, “and we’ve got to change direction or we will surely perish as a company. She turns her attention to Mr. nAch, and thinks about her frustration with how driven he is to succeed. She appreciates his drive, and sees him as one of the most productive people she has ever met, but also feels like if he succeeds in his sales goals, the company will likely fail. “I can’t seem to get this through to him,” she thinks, “and I wonder how to help him see the bigger picture. If he does, and we can harness his enthusiasm to help affect change in the company, then we have a good chance of success.” Ms. nPow then begins to think about other people in the company and how she can influence them to help the company shift gears toward a new product line and new strategy.

These three vignettes are not just about what people think in their cars that day. The kinds of thoughts, the themes of the thought, what each person sees as important and meaningful, will play themselves out repeatedly, throughout these three people’s lives. Mr. nAch has developed what are technically referred to as neuro-networks that unconsciously pattern his thoughts around how to do things better. Mr. nAff’s neuro-networks unconsciously pattern his first concerns around relationships. Ms. nPow’s neuro-networks revolve around influence and having an impact on her world. It is both reasonable to conclude and more importantly, we have empirical evidence to categorically prove, that they will adopt different patterns of behavior.

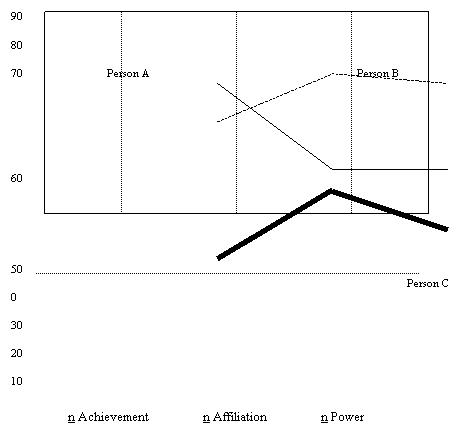

The Motive “Signature”

We describe each of these three social motives in order to accentuate their differences. In fact, everyone has each of these needs in varying degrees, and indeed, one can be high in all three. In other words, the amount of need one has is not a zero sum situation. and the relative amounts of each of these we have represents our motive profile. Because we each have distinct and different profiles, these differences make up what we might refer to as a motive “signtoature.” It is this signature that, in part, makes us each unique in terms of our personality.

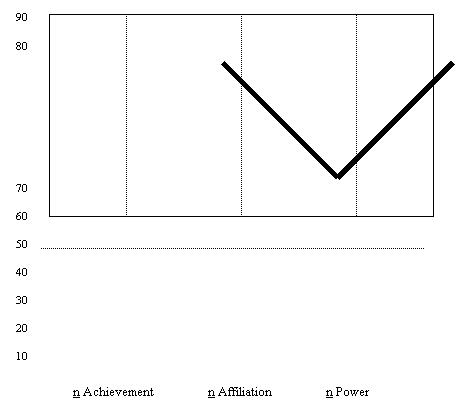

Figure 5. Three Different Motive “Signatures”

As will be demonstrated below, these social motives have significant implications for ones leadership style. For example, contrary to popular belief, high nAch people do not always make good leaders. In fact, an individual’s need to achieve can result in behaviors that unintentionally undermine the drive in others to achieve by overly competing, or by overly controlling a given situation. In addition, contrary to popular belief, high nAff leaders also do not always make good leaders. Sometimes, in their strong preference for harmony, for example, they avoid conflict, and sometimes these conflicts are a necessary and important part of organizational life. At the same time, in the right setting, high nAch leaders and high nAff leaders can be very effective. Where immediate results are needed, and where positive models of the achievement drive is needed, high nAch people can often thrive. And where the job requires the leader to integrate different functions and promote teamwork, high nAff leaders can be particularly effective. Ultimately, however, to understand leadership fully, we must understand the nature of power, for it is power and influence that moves people, organizations, and society as a whole when it cannot be done simply by example.

Does a Strong Power Motive Mean You’re a Good Leader?

One might be tempted to jump to the conclusion that a strong power (nPow) motive – the desire to influence others — makes for a good leader. As will be shown, a natural power motive helps, but isn’t required so long as you develop a conscious ability to influence others. This can evolve over time.

To understand power in action as it relates to leadership, an early study by D. G. Winter,[1] an associate of McClelland’s, is instructive. To test the impact of power on others, Winter examined the effect of Kennedy’s inspiring inaugural address on others. Messages that inspire others are, by definition, designed to influence and are therefore power driven. He found in his study that students exposed to Kennedy’s address were uplifted by his message. After hearing the address, their frequency of power thoughts as measured by a test called the Thematic Apperception Test statistically increased. This is significant from the point of view of leadership because people who are positively influenced by power often feel stronger, more capable, and take more actions to reach organizational aims. To explain his findings, let’s first draw upon McClelland’s explanation of the difference between a high nPow manager versus a high nAch manager. This explanation is taken directly from one of his most famous Harvard Business Review Articles: Power is the Great Motivator.[2]

Consider the case of Ken Briggs, a sales manager in a large U.S. corporation who joined one of our managerial workshops. About six years ago, Ken Briggs was promoted to a managerial position at headquarters, where he was responsible for salespeople who service his company’s largest accounts. In filling out his questionnaire at the workshop, Ken showed that he correctly perceived what his job required of him, namely, that he should influence others’ success more than achieve new goals himself or socialize with his subordinates. However, when asked with other members of the workshop to write a story depicting a managerial situation, Ken unwittingly revealed through his fiction that he did not share those concerns. Indeed, he discovered that his need for achievement was very high – in fact, over the ninetieth percentile – and his need for power was very low, in about the fifteenth percentile. Ken’s high need to achieve was no surprise – after all, he had been a very successful salesman – but obviously his motivation to influence others was much less than his job required. Ken was a little disturbed but thought that perhaps the measuring instruments were not accurate and that the gap between the ideal and his score was not as great as it seemed.

Then came the real shocker. Ken’s subordinates confirmed what his stories revealed: he was a poor manager, having little positive impact on those who worked for him. They felt they had little responsibility delegated to them, he never rewarded but only criticized them, and the office was not well organized but was confused and chaotic. On all those scales, his office rated in the tenth to fifteenth percentile relative to national norms.

As Ken talked the results of the survey over privately with a workshop leader, he became more and more upset. He finally agreed, however, that the results confirmed feelings he had been afraid to admit to himself or others. For years, he had been miserable in his managerial role. He now knew the reason: he simply did not want, and he had not been able, to influence or manage others. As he thought back, he realized he had failed every time he had tried to influence his staff, and he felt worse than ever.

Ken had responded to failure by setting very high standards – his office scored in the ninety-eighth percentile on this scale – and by trying to do most things himself, which was close to impossible; his own activity and lack of delegation consequently left his staff demoralized.

Ken’s experience is typical of those leaders whose strong need for achievement combined with low need for power causes them to be frustrated with others and move toward a more coercive approach to leadership. Although Ken demonstrates power, it was not focused on the needs of others, but on his own needs. As a result, he uses power as a blunt sword. Like many high achievement driven people, Ken was very successful in his individual contributor role and, as a consequence, was promoted into a managerial position for which he, ironically, was probably not well suited. This explains a long misunderstood phenomenon as to why individuals who are highly productive in one job often demonstrate the “Peter Principle” when promoted into a management position.

Power Motive: Good or Bad?

A clear eyed view of the concept of motives must be taken to realize that none of the three motives, nAch, nAff, or nPow, are intrinsically “good” or “bad”. A power motive isn’t bad per se, unless it is used to accomplish bad things. Closer to the point is the notion that different motives and motive patterns tend to “fit” different situations better. The many traits of a power-motivated leader tend to fit the requirements of many (but not all) management positions. When it comes naturally, it works best, but the traits of a power motive can also be developed. Unfortunately, because power is such a loaded term for many and in our society often seen as undesirable, often people deny or don’t develop and refine their ability to influence others toward productive organizational outcomes.

What Kind of Power?

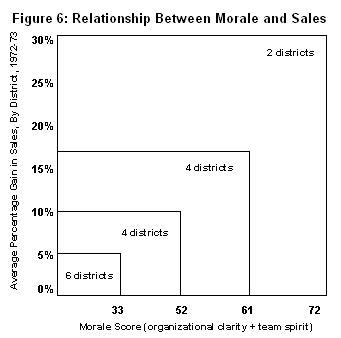

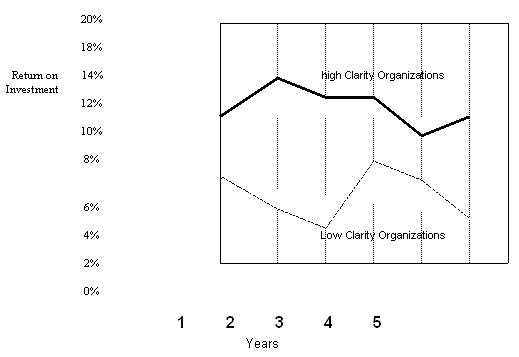

If achievement motivation does not, by itself make a good leader, asserted McClelland, socialized power likely will. To demonstrate this, 16 sales districts from a major U.S. company were tested and then rated for morale, as measured by the degree to which people were clear about roles, responsibilities, and organizational direction (referred to below as “organizational clarity”) and the degree to which there was strong and effective teamwork (referred to below as “team spirit”). The percentage gains and losses in sales for each district were then compared to their prior year. The difference in sales figures by district ranged from a gain of nearly 30% to a loss of 8% with a median gain of about 14%. The relationship between morale and sales was then ascertained showing a clear positive correlation.[3]

The motive scores of more than 50 managers of both high and low morale units were then examined, revealing an inescapable pattern. More than 70% of the managers in high morale units scored high in need for power. Moreover, the best of these managers, as judged by the morale of those working for them, tended to score the highest on power motivation. Still, the whole story is not revealed. 80% of the better managers had scores of power motive stronger than their need for affiliation as compared to only 10% of the lower performing managers. This pattern held true throughout the whole company. In the research, product development, and operations divisions, for example, 73% of the better managers had a stronger need for power than a need to be liked, as compared with only 22% of the lower performing managers.

Towards a Leadership Motive Pattern

McClelland’s most definitive study demonstrating the impact of the motive patterns on leadership was carried out at AT&T.[4] In their study, the careers of 311 entry level managers were tracked over a 16 year period. In this study, they hypothesized that managers whose predominant needs were high in socialized power and where those needs were higher than their need for affiliation would likely be more successful than others. We call this the leadership motive pattern – a “signature” of motives best suited for leadership. Their findings indeed reinforced the hypothesis. Those managers who were characterized by the leadership motive pattern at entrance to the company were more likely to be promoted to higher levels of management over time. Moreover, nearly half of the high level management people followed the leadership motive pattern. By way of contrast, those with high nAch profiles, while successful in lower management levels where technical skills were more important, tended to peak in their careers at lower levels and not move up the corporate ladder as readily.

In a similar study of successful Navy executive officers, the same leadership motive pattern distinguished the more effective Navy officers from their less effective counterparts. Interestingly, the characteristics of successful petty officers were similar, with two outstanding differences. Successful petty officers saw their work as oriented around getting things done (achieving) and relating effectively to others (affiliation), with less emphasis on the importance of getting things done through others. In other words, they did not see the game of “influence” as important as those that moved up the Navy’s organizational ranks.[5]

To further test the leadership motive pattern, McClelland and his associates distinguished between three kinds of managers—institutional managers, affiliative managers, and personal power managers:

*Institutional managers are high in power motivation, low in affiliation motivation, and high in inhibition, that is, able to consciously inhibit their personal ego gratification in lieu of seeking goals for the greater good.

*Affiliative managers have affiliation needs stronger than their need for power.

*Personal power managers have high needs for power, higher than their need for affiliation, while their inhibition score is low.

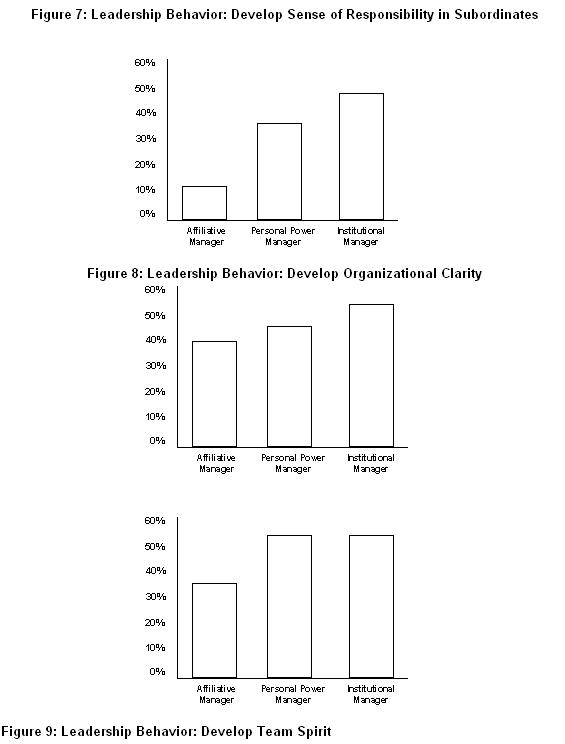

In one of McClelland’s most illustrative studies, he examined a Sales Division of a large company whose managers closely matched the three types above. By correlating the type of manager with three different features of an organization’s effectiveness, a clear picture of the efficiency of the institutional manager emerged.[6]

By further studying the behaviors that institutional managers tend to exhibit, McClelland found five characteristics that seem to distinguish them from the other types.

*They are more organization minded; they tend to join more organizations and feel responsible for building them. They also tend to believe in the importance of centralized authority.

*They report that they like to work—they like the discipline of work, and they like getting things done in an orderly way.

*They are willing to sacrifice their own self-interest to meet the needs of the organization. This is in contrast to the personal power manager whose own personal interests tend to be paramount.

*They have a keen sense of justice. They believe in fairness and that people who work hard and sacrifice for the good of the organization should get rewarded for their efforts.

*They tend to be more mature—less egotistic, less defensive, and more willing to seek advice from experts.

In summary, the above research seems to strongly suggest that, to be effective, a leader may need to possess a high need for power directed toward the benefit of the organization as a whole. Moreover, the need for power needs to be greater than his or her need for affiliation. A leader with a high and dominant need for affiliation will have a tendency to want to stay on good terms with all people and will likely make exceptions to corporate policies. In addition, it is often easy to recognize the affiliation motive in their desire to avoid interpersonal conflict. The desire to please will often result in an inability to provide focus and direction, and thereby cause confusion and loss of confidence. In addition, in their effort to please employees, they will likely apply policies differentially, causing mistrust on the part of others.

“to be effective, a leader may need to possess a high need for power directed toward the benefit of the organization as a whole”

To the undiscerning eye, these findings might be interpreted to conclude that to be an effective leader, one must have a high need for power, and without it, you will likely be ineffective. This would be an overstatement of the case. Rather, the findings suggest that power is (unconsciously) a primary factor in most leaders’ effectiveness, and the effective and mature expression of power is likely to yield positive results in many, if not most, leadership situations.

“…power is (unconsciously) a primary factor in most leaders’ effectiveness, and the effective and mature expression of power is likely to yield positive results in many, if not most, leadership situations.”

What If You Have a Low Power Motive?

If the need for power is not present in your motive pattern, and it is needed for you to be an effective leader, the game is not lost. The challenge for you may be to consciously think more about how to influence others, a thinking pattern that others high in nPow do more subconsciously. This will enable you to cultivate your ability to express power more effectively and thereby level the playing field in terms of producing more influence behaviors.

While McClelland’s findings clearly suggest that people with high nPow tend to be more effective as leaders, the behaviors that are exhibited by high nPow individuals are paradoxically often seen as undesirable in our society. As a society, we tend to have contradictory feelings about power. We both want it, and yet don’t want to be affected by others who want it. We respect people who get things accomplished, yet often resent their approach.

The distinction between personalized power and socialized power is particularly important here because it sheds light on the paradox. People who are high in personalized power tend to see the world as a win-lose game. “Survival of the fittest” is their credo, and they will do whatever it takes to get ahead. They tend to like prestige and, in the extreme, tend to be impulsive in their application of their power needs. This invites resistance to them and their goals.

In contrast, people who are high in their socialized power needs often exercise their power for the benefit of others. They seek win-win solutions to conflict and tend to effectively suppress their inner need for domination. Hence, they tend to be much more effective in their organizational leadership than their personal power counterparts and exhibit behaviors that are, more often than not, seen as socially desirable. This invites support to both them and their goals.

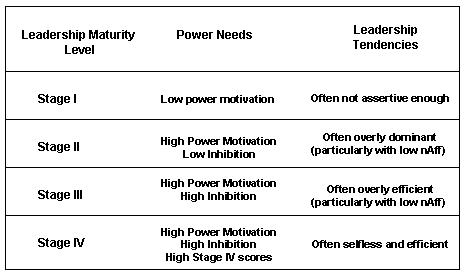

This distinction became particularly compelling to McClelland later in his research career when he became interested in the question of whether and how power needs differ as people mature. In exploring the question, he distinguished between four different stages of maturity as they relate to power needs.

Figure 10: Relation of Power Motivation and Inhibition to Maturity and Leadership Potential

McClelland hypothesized that these stages, in effect, form a natural hierarchy of power, where each stage represents a “more mature” approach to power and influence and will therefore result in greater leadership capability. He formed his hypothesis by observing and comparing people who used fundamentally different leadership styles and their relation to power.

Later, research on how people progress through different stages of ego maturity and their relationship to power and influence strongly corroborated McClelland’s assertion. In each of the studies described below, ego maturity is measured by the degree of complexity in ones thinking, the ability to differentiate among multiple feelings, the ability to recognize and value differences between ones view and that of others, and the ability to focus on the long term, rather than strive solely to meet immediate needs.

In a study by S. Smith,[8] she found that people with more mature egos tended to be less driven by their needs for personal power and control and more by their need to focus on the needs of others and the organization as a whole. In contrast, people with less developed egos tend to exercise coercive power—that is the need to control others and their actions. As managers they tend to prefer to enforce decisions rather than make them. They tend to think in terms of right or wrong, and are often extremely rule bound.

In a similar study, H. Lasker[9] found a clear relationship between ego maturity and motive patterns. He found that managers at lower stages of ego maturity tend to have stronger personal power drives while managers with greater ego maturity tend to be more driven by their needs for achievement.

Inspired by these findings, W. Torbert found a strong correlation between ego maturity and progression up the corporate ladder of success.[10] In another study, W. Torbert and D. Fisher found that leaders with higher ego development were far more capable of exercising socialized power and leading organizational change efforts than their less mature counterparts.[11]

Daniel Goleman and his colleagues at the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations at Rutgers University, have re-labeled nPower as “Social Skills,” in his Harvard Business Review article. He defines this as “friendliness with a purpose, moving people in the direction you desire.” This is as close to McClelland’s definition of Power as one can get.[12]

The above research, while strong in their implications of which profile will likely result in more effective leadership, does not suggest that only one motive pattern will yield leadership success in all cases. Other motive profiles may also be more likely to be effective in different situations. For example, the role of integrator is a critical organizational function, especially important in organizations that require cross functional communication. In this case the integrative leader is one who facilitates communication across organizational lines and helps groups work through conflict. In a study by P. Lawrence and J. Lorsch, they found that effective integrators differed from their less effective counterparts by their higher need for affiliation.[13]

They pay more attention to others and their feelings, they try harder to establish friendly relationships in meetings, and they take on more assignments that offer opportunities for interaction. In addition, they tend to have average, but not high needs for achievement as well as average, but not high needs for power. In other words, effective integrators have balanced motive profiles and their affiliation needs are higher than those that are ineffective integrators. McClelland drew a similar conclusion in a study of 96 Navy Human Relations officers, where the most successful ones displayed moderate and balanced needs for Achievement, Affiliation, and Power. He called this the integrator motive profile.[14]

Power Is Great For Leaders, But What About Affiliation?

As organizations have become less hierarchical, it appears that the implications of McClelland’s early research for today’s leadership may need to be revisited. While the ability to influence others continues to be a critical source of leadership effectiveness, the ability to establish collaborative relationships has become more and more important in the past decade. Hence, some combination of socialized power with medium affiliation drives may be the profile needed to succeed in many of today’s flatter, more collaborative environments. As leaders need to become more facilitative rather than authoritative in their orientation, so too must their profile change. This flies in the face of McClelland’s earlier assertion that in order to be effective, a leader has to have need for power stronger than their need for affiliation. This may still be true, yet a potent dose of nAff is extremely important to be a good facilitative manager.

So which is it? Does a good leader need to be low in affiliation needs relative to power, or does he or she need a medium or even higher amount of nAff? And where do standards come from if achievement is not high?

To shed light on this issue, R. Boyatzis, former President of McBer, the consulting firm founded by David McClelland, made a distinction between two types of affiliation needs—affiliative assurance and affiliative interest. The need for affiliative assurance is based on the need to be liked and approved by others and often results in behaviors designed to avoid rejection. The need for affiliative interest, in contrast, is based on a genuine concern for others and their well being and often results in “joining” behaviors such as being involved in teams, social clubs, etc. One motive is self-focused (affiliative assurance), the second is other-focused (affiliative interest).

In a working paper on the subject, Boyatzis hypothesized that the affiliative assurance manager will likely behave in ways that are counterproductive to organizational needs.[15] He would make decisions seeking acceptance and approval from others rather than make tough decisions. He would equate harmony with success rather than performance with success, and would feel uncomfortable confronting others for fear that they would lose others’ approval. In contrast, a manager driven by affiliative interest will likely be compassionate, yet direct in their decision-making and less concerned about the consequences of making tough decisions.

While there is no direct research to date on the subject, C. Lafferty and his associates have for many years been studying the relationship between 12 different personality traits and leadership effectiveness. Their research has strongly corroborated Boyatzis’ hypothesis. Two of Lafferty’s 12 personality traits make the same distinction as Boyatzis, and in multiple studies, Lafferty found that strong leaders exhibited low needs for approval, and high needs for affiliation—that is, a high interest in and care for the needs of others. Moreover, they tended to express that concern as a leader through coaching of others toward increased performance.[16] This is distinct from coaching that is driven by the desire to maintain a relationship.

Conclusion – Motives and Leadership

When taken as a whole, the research on motives as it relates to leadership forms a compelling guide. The research is telling us that people do have different needs, perceptions, and drives. At a deep unconscious or pre-conscious level these form the basis for their leadership style. We have come to refer to this as being on “automatic pilot.” While no style is perfect, and each style can be effective in different situations, the task of a leader is quite clear: to get the most out of ones people, and to sustain their performance over time. To do this, a leader must have influence, and must think about the motives of his or her people, and how they will respond to his or her leadership differently based on these motives. This influence must be directed toward the greater good of the whole or people will resist it. Moreover, leaders’ attention to influence must outweigh their need to be liked. If their need for approval is too strong they will not make difficult decisions, ones that are unpopular. And these decisions sometimes have to be made for the greater good of the whole. Finally, a leader has to have some achievement drive, which produces the thinking patterns from which high standards emanate.

We have come to refer to this as being on “automatic pilot.”

These leadership principles do not stand alone. When applied in a mature fashion, a leader can directly and significantly impact the climate of the organization as a whole. Certain leadership styles impact the climate differently, which in turn affects and directs the attention of people in the organization. In the following section, we will look at this relationship, and begin to see a clear picture of the kind of leadership style that most powerfully affects and creates an organizational climate for success.

Part II

THE LEADERSHIP CHAIN CONTINUED:

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STYLE AND CULTURE

Organizations and their cultures do not just emerge overnight. They build and evolve over time. They evolve as a result of the personality of the leaders, the environment in which the organization exists—its geographical location, its industry, etc.– and the key decisions it makes that determine its history.

We define “culture” as “the way we do things in this company in order to succeed.” As previously stated, we are focusing on climate variables which we define as “the subset of measurable variables in the culture that affect motivation.” These are the factors that influence an organization’s effectiveness and its results over long periods of time.

Of all the factors that determine how and why a particular organizational culture emerges, perhaps the most powerful impact is the style of the leader. The leader of an organization, by virtue of his or her personality and behavior, makes an indelible mark on the organization’s culture, either consciously or unconsciously. People in organizations are constantly adjusting to the expectations of the leader. They are looking to the leader for signs of what is okay to do or not to do, they pay attention to what the leader ignores and what the leader focuses on, and they are following the example she provides. In other words, a leader cannot help but directly impact the culture/climate of her organization.

Witness the case of Southwest Airlines. As a company, its people are known for their enthusiasm and playfulness, and unique way of operating. When you fly on one of their airplanes, its spirit is palpable. Etched on the walls are its motto: “nourished by our people’s indomitable spirit, boundless energy, immense goodwill and burning desire to excel.” Anyone who has ridden on a Southwest Airlines plane knows what we mean here as they are treated to playful, humorous, and often counter-industry comments of the flight attendant manning the microphone during takeoff and landings. Not surprisingly, the organizational climate of Southwest Airlines mirrors the personality of its leader—Herb Kelleher. Kelleher is known far and wide as a fun loving, aggressive, hard drinking president, who is adulated by the people in the company for his good heart, and playful leadership. Hence, in this example, and countless others throughout corporate America, the quality of leadership and the character of an organization’s culture appear to be inexorably linked.[17]

In this, the second part of the article, we explore the second link of the leadership chain: namely the relationship between a leader’s style and the climate of the organization. It is this link that we are most familiar intuitively, yet at the same time, we fear. When we were at the individual contributor level in the organization, we blamed upper management for what ails the corporation. Now in the role of leader, we have no where to turn to blame the dysfunctional features of the organization except ourselves.

While we use well known publicized case studies such as Southwest Airlines (Herb Kellerher), WalMart (Joe Walton), IBM (Thomas Watson) and Microsoft (Bill Gates) to demonstrate the forceful impact a personality has on the organization, it is often less clear in your system. That is not because it is less impactful, but rather that it is hard to distinguish day to day behaviors we become used to as seminal in the organic behavior of the entire system.

What the Research Shows

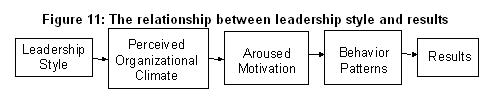

One of the earliest attempts to understand the linkage between leadership and organizational climate was the research of two colleagues of McClelland’s: G. Litwin and R. Stringer. In their work, Litwin and Stringer began with the assumption that the success of an organization is dependent on the behaviors of its people, and that the most powerful determinant of those behaviors is the degree to which people’s motives are aroused.

An aroused motive is like an itch that needs to be scratched. When a motive is aroused, people behave to meet the needs of that motive. For example, if affiliation is aroused, then people will want to be with others, to interact socially. If a power need is aroused, they will want to control or influence others. If achievement is aroused, people will want to be more productive, innovative, and goal directed—to achieve something of value. Of the three motives, the achievement motive is most likely to be correlated with individual performance. In other words, the more the achievement motive is aroused in individual contributors, the greater the impact on organizational productivity.

Based on this aroused motive premise, Litwin and Stringer then hypothesized that certain climates tend to stimulate or suppress certain motives and that different leadership styles will create different climates. Their causal chain of logic – quite similar to that of the Leadership Chain — is explained in the following figure (figure 11).

To test their hypotheses, Litwin and Stringer began to experiment with a number of different variables to measure organizational climate. They drew the conclusion there are a discreet set of characteristics that are most critical to the productive functioning of an organization.[18]

- Conformity* (originally referred to as structure) – the feeling that employees have about the constraints in the group, how many rules, regulations, procedures there are; is there an emphasis on “red tape” and going through channels, or is there a loose and informal atmosphere.

- Responsibility – the feeling of being your own boss; not having to double-check all your decisions; when you have a job to do, knowing that it is your job.

- Reward – the feeling of being rewarded for a job well done; emphasizing positive rewards rather than punishments; the perceived fairness of the pay and promotion policies.

- Risk – the sense of riskiness and challenge in the job and in the organization; is there an emphasis on taking calculated risks, or is playing it safe the best way to operate.

- Warmth – the feeling of general good fellowship that prevails in the work group atmosphere; the emphasis on being well-liked; the prevalence of friendly and informal social groups.

- Support – the perceived helpfulness of the managers and other employees in the group; emphasis on mutual support from above and below.

- Standards – the perceived importance of implicit and explicit goals and performance standards; the emphasis on doing a good job; the challenge represented in personal and group goals.

- Conflict – the feeling that managers and other workers want to hear different opinions; the emphasis placed on getting problems out in the open, rather than smoothing them over or ignoring them.

- Identity – the feeling that you belong to a company and you are a valuable member of a working team; the importance placed on this kind of spirit.

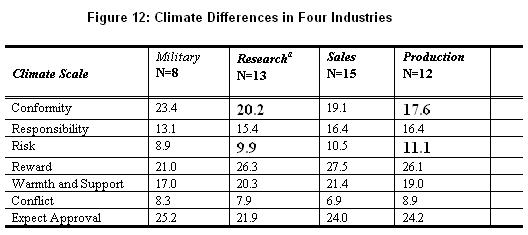

They then determined that the best way to test the validity of these variables was to see whether and to what extent different organizations differ along these variables. They found, for example, that in the 13 research organizations they examined tended to be high in perceived conformity (20.2) and low in risk taking (9.9). In contrast, the 12 production organizations were lower in perceived conformity (17.6) and higher in risk tendencies (11.1). The following table depicts their early results.[19]

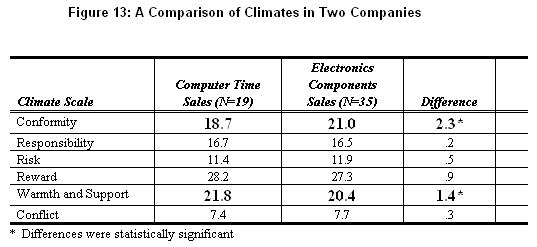

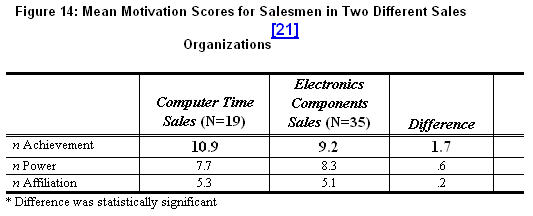

To study the impact of organizational climate on the motive drives of people, they then studied two sales organizations thought to be quite different in organizational climate. The first sales consisted of 19 sales people from a computer sales company; the second organization consisted of 35 sales representatives from an electronics components firm. While both organizations had much in common in terms of the types of people who staffed them, the markets they served and the salaries sales people earned, they differed considerably in terms of the climates that characterized them. The computer time salesmen, for example, were managed in a way that emphasized personal relations while the electronics components sales people were managed in a way that encouraged aggressive selling techniques. Here then, are the differences in climate as measured by the above climate variables:[20]

While many climate characteristics were similar, the two climate scales demonstrably different were Conformity and Warmth and Support. As you might predict, greater room to make choices (lower conformity) combined with greater expression of support and care yielded a higher achievement climate.

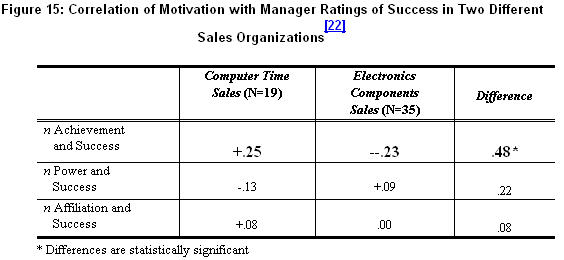

Moreover, when asked to rate the success of the salesmen on a four-point scale, it became clear that greater achievement motivation scores yielded higher success. This makes good sense, for the quality and characteristics that describe nAch drives are also the same that are associated with effective goal driven behavior.

“the quality and characteristics that describe nAch drives are also the same that are associated with effective goal driven behavior”

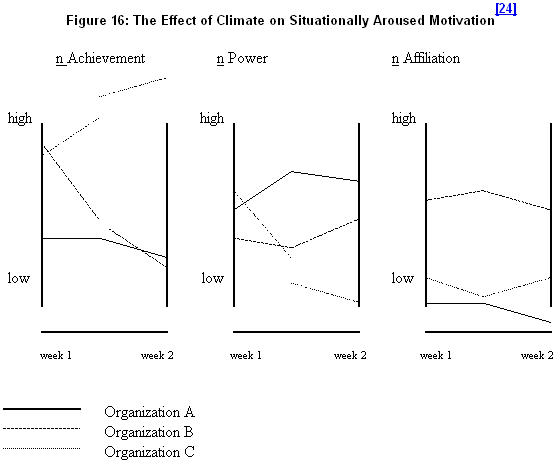

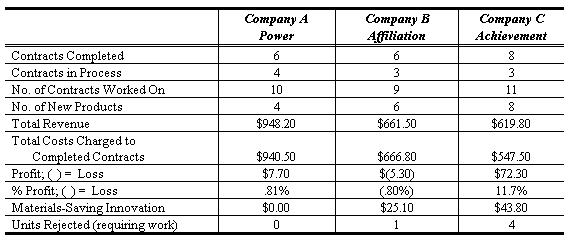

To test the influence of leadership style on organizational climate, Litwin and Stringer then created three simulated business operations (described as organizations A, B, & C) made up of 15 members, each headed by a president.

The presidents were instructed regarding the leadership style they were to maintain so that leadership style became the major variable input. All other factors were controlled as carefully as possible. The physical locations were identical, the technology and essential tasks were the same, and the members of the organizations were matched with respect to age, sex, background, motive patterns, and personality characteristics. The following description is drawn directly from Litwin and Stringer:[23]

Each simulated business operated in a 100-seat classroom. The work involved the production of miniature construction models of radar towers and radar-controlled guns of various kinds from “Erector Set” parts. A typical product was comprised of from 30 to 50 parts. Innovations were called for, and none of the businesses could afford to stand still.

15 subjects were assigned to each business including 13 men and 2 women. The subjects ranged in age from 18 to 29 years. All were hired (at an average hourly wage of $1.40) to participate in a study of “competitive business organizations.” 45 subjects were selected from an initial subject pool of 78 because they composed the “best” matched groups. The dimensions along which the groups were matched were: age, college major, business or other work experience, n Achievement, n Affiliation, n Power scores, and California Psychological Inventory personality profiles (particularly overall elevation, and elevation in the major areas). Attention was given to careful matching with respect to initial motive score, since aroused motivation was a major output measure.

The experiment was conducted over a two-week period, comprising eight actual days of organizational life. The workday averaged about six hours. During the course of the experiment, daily observations were made, and periodic readings were taken using questionnaires and psychological tests. These data were used to provide feedback to the presidents indicating to what extent they were achieving the intended leadership styles.

The leader of Organization A was instructed to place strong emphasis on the maintenance of a formal structure. The leader of Organization B was instructed to create a loose, informal structure stressing friendly, cooperative teamwork. The leader of Organization C was instructed to place high emphasis on productivity, encouraging people to set their own goals and take personal responsibility for results.

Litwin and Stringer hypothesized that the leadership style of leader A would create a climate that stimulated the need for power while the need for achievement and for affiliation would be reduced. Leader B would create a climate that would arouse the need for affiliation, while power would be suppressed. And finally Leader C would create a climate that would arouse the need for achievement while the need for affiliation and for power would be unaffected.

Not surprisingly, over the two week period, each organization developed distinct organizational climates as a result of the different leadership styles. While not all of the initially hypotheses were confirmed, the most salient result of the study was that the leadership style and its resulting climate of Organization C far more than the other two aroused the achievement drives of the people in the organization. At the same time power drives that tend to be counterproductive were stimulated by the leadership style of Leaders A and B. Affiliation drives were relatively unaffected. As a result, profitability in organization C was far greater than A and B (explained more fully in the third section of this article).

Tests of social motives administered several weeks later corroborated these findings, strongly suggesting that not only does the leadership style affect the climate and therefore the aroused needs of people, this affect can be long-lasting.

After several more studies on the relationship between corporate climate and success, Litwin and Stringer modified their original set of climate variables, and eventually landed on the following six as representing those variables that most impact long term organizational performance. These six will be referred to for the remainder of this article.

The Six Leadership Behavior Styles

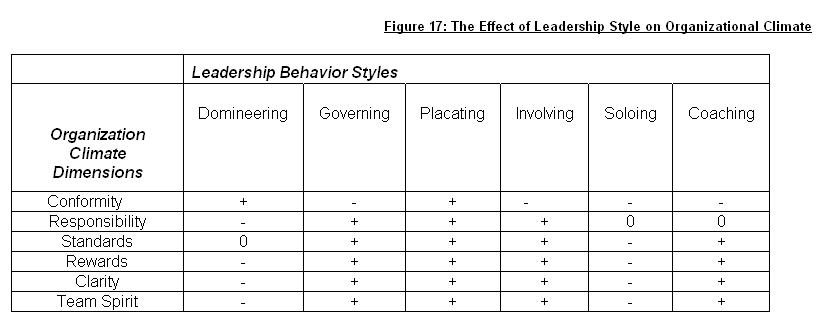

The following six distinct leadership behavior styles have the greatest impact on climate and thus long term organization performance:

Domineering: Demands immediate compliance, controls tightly, gives corrective negative feedback

Governing: Gives long-term direction and vision, accepts input, gives balanced feedback

Placating: Promotes harmony, considers people’s feelings as strongly as the task, gives inconsistent or exclusively positive feedback unrelated to performance

Involving: Works for collaborative commitment, empowers others to act, gives feedback for adequate performance rather than clearly differentiating levels of performance

Soloing: Works to own high standard, ignores or micro-controls depending on assessed quality of employee, gives no feedback, has trouble delegating

Coaching: Develops employee for long term, empowers to learn and develop, gives feedback on performance for improvement

These styles have as their origins the thought processes of the motives. The “raw style” from nAch is Soloing, from nAff is Placating and from nPow is Domineering. The “learned style” from nAch is Coaching, from nAff is Involving and from nPow is Governing. With few exceptions the “learned” (adapted) style is more effective and appropriate than the raw style.

In a recent study, researchers at McBer found a strong relationship between specific leadership styles and the six important organizational climate dimensions, further corroborating and building on Litwin and Stringer’s findings.[25] For this study they used a measure of managerial style that distinguishes between six differing approaches.

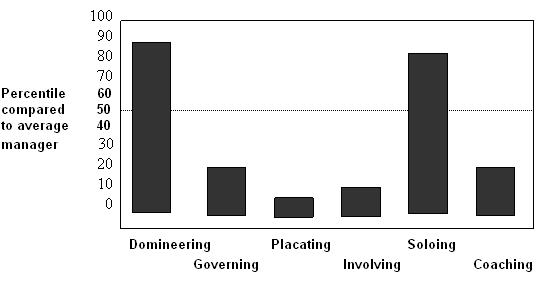

An analysis of 3871 managers and executives of major international companies in 9 different industries who rated their immediate supervisor between 1986-1992 found that domineering and soloing styles of management tended to correlate with low achievement climates, while the use of governing, placating, involving and coaching styles tended to correlate with higher achievement climates. In particular, the data showed the following effects on climate variables.

Equally as significant is the fact that differences in managerial style account for between 54% and 72% of variance in climate. In other words, far more than any other factor, one’s management style affects the climate of your immediate work group. This is particularly interesting when one thinks about how often managers say they are powerless to affect their organization and its results. They complain that their manager ties their hands, that the company’s policy inhibits their performance, etc. This data shows, to the contrary, that their ability to influence their organization lies squarely on their shoulders.

To understand this relationship more fully, let’s look at a couple of actual leaders, each demonstrating different leadership approaches.

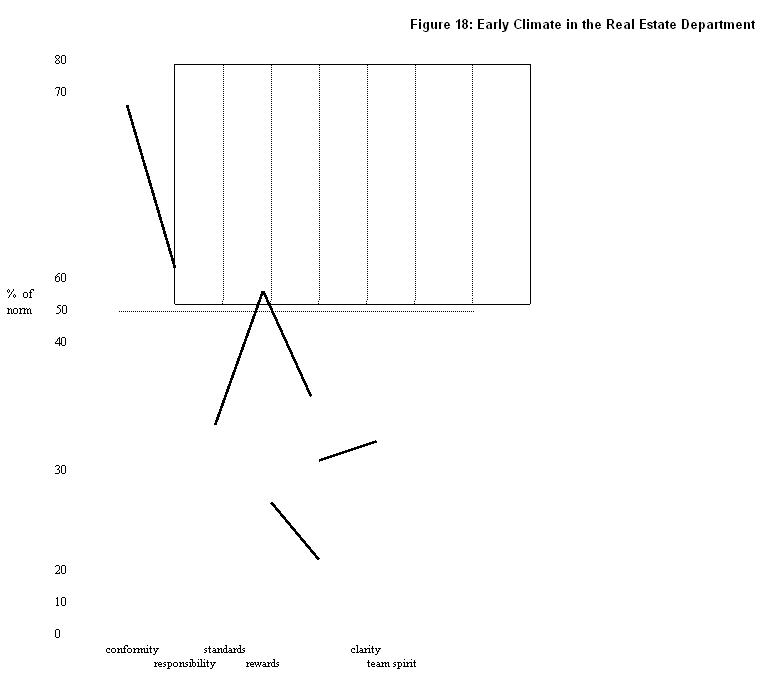

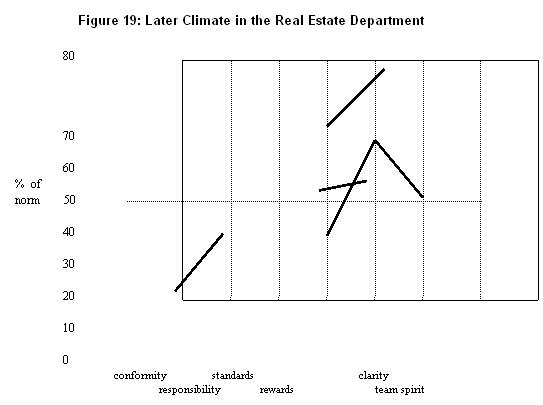

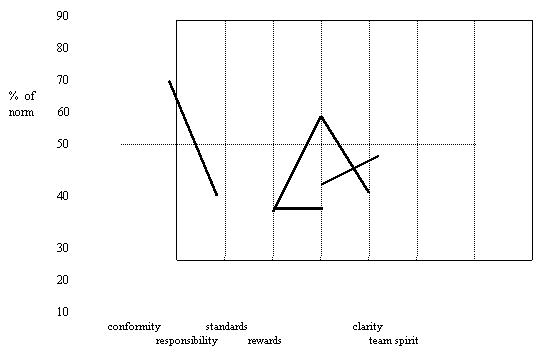

Bill Toomey is the head of the Real Estate Department of a Fortune 500 electronics company. For a long time he was highly successful as an individual contributor in the company, and was eventually promoted to his position as manager of the department due to his individual skills and enthusiasm. However, because he was so achievement driven, he tended to use a soloing style of management. He would often show his direct reports how to best make real estate deals, and interceded when he thought he could do it better. Moreover, he often criticized them when they made mistakes, even minute ones. Because of his micro-management style, many of his direct reports felt belittled by him. While Bill thought he was coaching, they felt judged and undermined by his over-controlling presence. Interestingly, by his own admission, he “took over” too much, but he could not help himself. He genuinely thought he could do it better, and that by showing them the way, he was helping his direct reports become more effective. They, on the other hand, felt like they had little room to maneuver, and little room to influence the direction of the department or the key decisions. Moreover, when things got tight, Bill would revert to a domineering style of management, thereby exacerbating the feeling of “no freedom to move” and too much micro-managing.

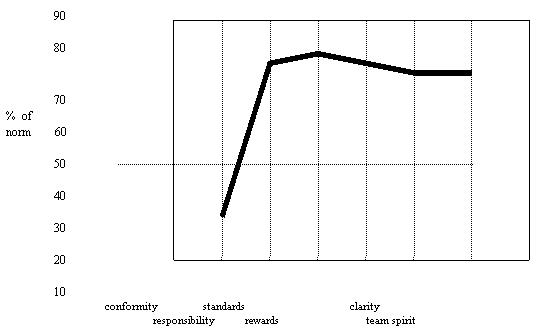

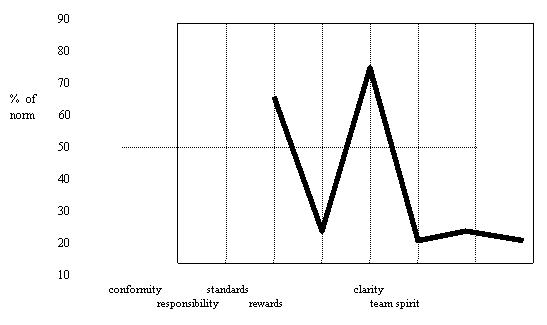

When tested with a normed survey, the results showed that they felt they had to conform to Bill’s rigid expectations, that they had little responsibility for the department and its results, they were unclear about their roles and responsibilities, and team spirit was at an all time low.

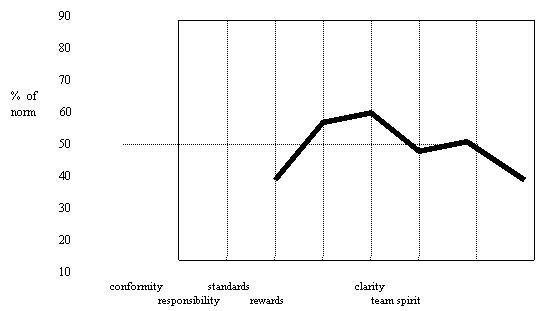

In a workshop designed to learn about the leadership chain and the impact Bill had on his organization and its results, Bill looked closely at how he was creating such an achievement depressed climate and sought ways to change his leadership style to more positively impact the climate. He quickly decided that, in spite of his own needs to drive toward personal excellence by demanding compliance, in the long run results would improve if he increased: 1.) the degree to which he gave others authority and autonomy to make decisions, 2.) the degree to which he included them in the overall direction of the department and 3.) coached them towards increased performance, rather than do it for them. As a result, in 6 months, the climate dramatically improved. Conformity went down (due to less domineering leadership), standards, rewards, clarity, and team spirit increased significantly.

While the overall performance results are not yet in, the improved climate of the organization as a direct result of Bill’s shift in leadership has already paid off. One of his employees, for example, just closed a major, multi-million dollar deal; the biggest he had ever done and the most successful. Said the employee, “I felt I was over my head in the deal. I had never done such a deal, and Bill gave me room to do it. I really rose to the occasion.” This would likely not have occurred under Bill’s previous leadership style.

In our experience working with thousands of managers and executives, we have seen dramatic results time and time again. The above early studies on leadership and organizational climate keep showing us that not only does ones leadership make a difference, changes in leadership style produce rapid and often significant improvement in its results. The key is knowing specifically where and how to make the changes.

“far more than any other factor, ones management style affects the climate of the organization”

In related studies by other researchers, the relationship between leadership style and organizational climate continues to show the same patterns. For example, in studies by Clayton Lafferty (a student and colleague of McClelland’s), he and his associates have found a direct correlation between leaders who care about their people, who establish challenging, yet achievable goals, and who rarely use coercive means to achieve these results, are consistently seen as more effective leaders than others. Moreover, they create climates that tend to perform more consistently and effectively over long periods of time. Similarly, John Kotter has drawn the same conclusion from his studies of the differences between leaders and managers. Their long term focus, ability to invite and sustain organization change, and their powerful vision distinguishes effective leaders from their less effective counterparts.

Conclusion

The second link on the leadership chain is now secured. It has shown us that while different leadership styles work in different situations, there is a particular style that is likely to produce greater goal attainment in most business situations. This style is visionary (governing), involving, and encourages others to learn, grow, and achieve great results through coaching. While variations do exist, few leaders will go wrong in adopting this approach.

Perhaps, even more significant is the compelling findings of the more recent McBer study that shows that the leader’s style accounts for over 50% of the variance between climates. In other words, as a manager, no longer can we blame the organization above us for the quality of the organization below us. We can and do directly impact our organizations, our departments and our teams by the kind of leader we are. If we want more results, and we want these results to sustain, the most powerful lever for change is our leadership behavior.

Part III

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ORGANIZATIONAL CLIMATE AND PERFORMANCE

So far we have explored the relationships between the first three links on the leadership chain. We have seen how the motive profile of a leader impacts his or her leadership style and that his or her style influences the organization’s culture. In this third section, we will explore the relationship between the third and fourth links on the leadership chain: namely the relationship between an organization’s culture and its success.

As we have previously indicated, for the purposes of this article we will limit the discussions of Dr. Schneider’s research on culture to the variables that impact motivation. This will focus us on the subset of variables originally labeled “climate” by Litwin and Stringer. An extremely important conclusion of Dr. Schneider is that each of the cultures that is “in balance” (therefore effective and productive) has the same climate which we will refer to as “achievement aroused.” While this makes sense in retrospect, it is a relatively new finding with major implications, particularly for today’s knowledge based companies.

While claims abound about the relationship between an organization’s climate and its performance there is surprisingly little published research evidence to support this claim. Fortunately, the evidence that does exist is extremely compelling.

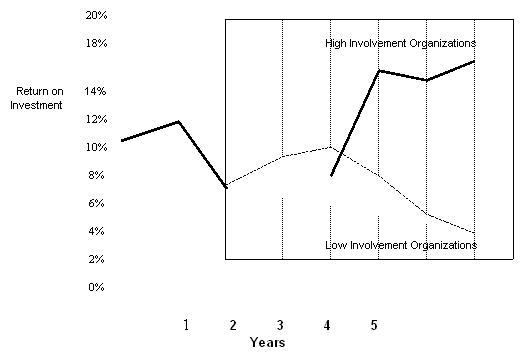

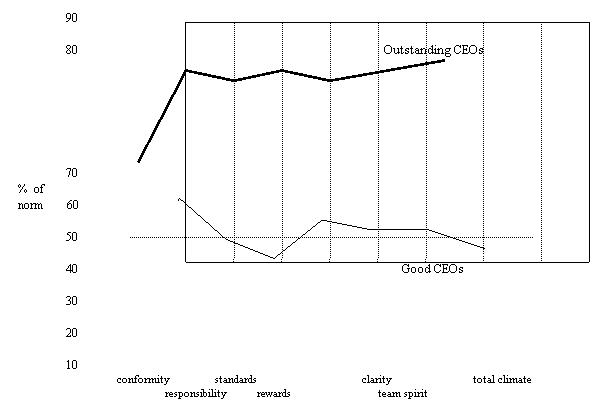

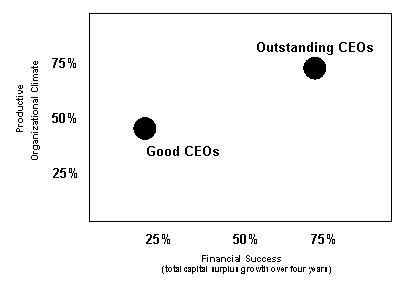

The Impact of Climate on Performance